Last Updated on September 9, 2015 by Steve Hogg

This post is about knee pain manifesting as an overuse injury. It is not about knee pain caused by sudden trauma like bike crashes. There is a section at the end about pre exisiting knee injuries, but the major thrust of this post is overuse injuries to the knee caused by the repetitive action of cycling.

Some years ago I gave a presentation at a sports medicine conference. I arrived early and listened to the entire presentation before mine which was given by a Norwegian based Aussie physio named Ben Clarsen. Ben was a physio for the pro team Francaise des Jeux at the time and his address was about the frequency and severity of injuries amongst the riders of the top 5 UCI ranked pro teams over a year, measured in terms of enforced time off training and racing. Ben had surveyed the 5 teams medical staff about this and his report was the highlight of the weekend for me.

According to Ben’s survey, low back pain was the most common problem and over a full year, the top 5 UCI ranked teams lost 2 – 3 days of training or racing per rider due to low back pain. That doesn’t mean that every rider experienced low back pain, though 40% did. What it means is that if there are 30 riders in a squad, then a total of 60 – 90 total rider /days of training or racing were lost annually due to low back pain. Knee pain was the next most frequent occurrence with something like 32% of riders experiencing knee pain over a year. However, the effects of knee pain on training and racing were more severe than low back pain, with the average amount of time lost to training or racing being 10 – 12 days per rider across the squads. To put that in perspective, knee pain was the major reason for injury related time off the bike. Knee pain resulted in 4 to 5 times more enforced time off the bike than did low back pain.

Bear in mind that these are pro riders on top squads who are self selecting to a degree. If they couldn’t do what they do, they wouldn’t be there. Offsetting this natural selection to some extent is the much higher training load than that undertaken by club racers and recreational cyclists.

A related conundrum is that while knee pain is the most frequent cycling related injury, it is also the most common exercise recommendation by the health profession for anyone recovering from knee surgery. During my fit client interviews, a substantial minority mention knee pain or knee niggles as the major reason, or one of the reasons for their visit to us. Why knee pain can occur while cycling will be the focus of this post and funnily enough, in most cases, cycling related knee pain doesn’t have much to do with knees. Instead it has everything to do with how the knees are loaded.

When we ride a bike the major joints being used to drive the pedals are the hip, knee and ankle / subtalar complex (which I’ll just call the ‘ankle’ for convenience. Here’s some video instruction about how each is constructed and works.

HIP JOINT

KNEE JOINT

ANKLE JOINT COMPLEX

I hope you have taken the time to watch the videos above. If so, the major thing I want you to take from them is that both the hip and ankle are joints designed to work in a multitude of planes, while the knee is more or less a hinge joint. It is only really designed to work in a single plane, more or less. It will tolerate some misalignment and is capable of some movement in other than a hinge like fashion but it is not particularly good at or designed for that kind of use under load or for a long period. The other thing worth knowing about knees is that crashes and trauma aside, bike related knee injuries are always overuse injuries and often creep up on the sufferer. Knees are held together with a lot of fibrous tissue; ligaments and tendons, which have little blood flow. That means that they are hard to injure but once injury occurs, need a lot of recovery, again because of the limited blood flow.

So how do knees become injured while cycling?

To restate what I’ve said above, knees work best in a single plane. Any influence or force that Challenges that ideal vertical, single plane, if repeated often enough will result in injury. A typical cyclist performs 5000 – 6000 pedal strokes; that is joint closing and opening cycles of the knee, an hour with a wide range of forces applied. So cycling provides plenty of scope for magnifying minor issues into overuse injuries. There are two basic categories of Challenge to ideal plane of knee movement on a bike; Mechanical Challenges and Functional (or Biomechanical if you prefer) Challenges. I’m going to work through the major Challenges one at a time. It is important to remember that often multiple Challenges are present in any individual case of cycling related knee pain.

MECHANICAL CHALLENGES

1. Cleat Rotational Angle: If your cleats are set at an angle that prevents the foot from sitting on the pedal at the angle that the body naturally prefers, then knee pain is often the result. If the foot cannot be angled as it needs to be, the knee is the weakest link in the pedalling chain and is loaded inappropriately. This is entirely preventable. The post Power To The Pedal – Cleat Position gives detail about how to determine the correct cleat angle in points 5 and 6 in italic script at the bottom of the article.

Sometimes the problem is that the pedal / cleat system being used does not have enough rotational movement to allow the riders feet to fall at the angle that they need to. Shimano Spd SL and Look Keo (grey cleat) have 4 – 5 degrees of rotational movement plus the ability to angle the cleat on the sole of the shoe. In addition, Speedplay Zero and Light Action cleats have 15 degrees range of potential rotational movement but no ability to angle the cleat. From time to time, I come across fit clients using one of these four systems, and occasionally other pedals, who cannot attain the angle of foot on pedal that their body’s prefer because of this. In these cases a change in cleat or pedal systems in necessary. For a minority of riders, a greater range of rotational movement is necessary. With Look Keo this means opting for the red cleats with 9 degrees of rotational movement. With Shimano there is no option with a greater range. With Speedplay, the cleats can be modified to a point, if you know what you are doing, but the best option is to change to the Speedplay X Series which have a greater rotational range.

I occasionally come across clients who are using cleats with zero freeplay. If you have reasonably good function and providing the cleats are exactly at the the angle that they need to be, no problem. However, too often in reply to my question of “Why fixed cleats rather than freeplay cleats?” I am told various paraphrases of “I don’t like my feet slopping around on the pedal”. I need to make it very clear that if your feet are moving around unnecessarily on a pedal or pedals, then there is something wrong with the way that you function, or your bike position, or both. All of these things have a solution. Usually that solution does not involve locking feet into what is often the wrong place on a pedal with a fixed cleat.

2. Cleat Position fore and aft: This is a huge variable. A cleat position that is too far forward may load the knee in susceptible people. I don’t see this often, but over time I’ve seen enough to know that it is a big deal for some. Any of the methods of determining cleat position outlined in Power To The Pedal will have only positive impact on the knees if applied correctly.

In contrast, while I’ve seen it, it is rare to find anyone experiencing knee pain from cycling with cleats too far back relative to foot in shoe.

3. Exiting the Pedal: My standard recommendation for males under 60kg and females under 65kg is to avoid using Shimano Spd SL and Speedplay Zero road pedals. Many people of small stature have to strain unnecessarily to exit these pedals with potential strain on the knee the result, particularly when the cleats are new . Not all riders below those body weights are affected but I’ve seen enough strained knees in lightweight, small stature riders that were caused in the attempt to exit these pedals to think it safer to make a blanket recommendation.

Speedplay Zeros have no means of reducing spring tension to make exiting the pedal easier, though I’ve got to say that pedal egress becomes easier as the cleats wear a little. Instead the smaller rider wishing to use Speedplays should choose either the Light Action or X Series models as safer options, as they are far easier to exit (and enter).

Shimano Spd SL’s do have the ability to reduce release spring tension but even the minimum tension setting is high enough to adversely affect the knees of some smaller riders. Again, cleat wear reduces the potential for problems which often reappear every time the cleats are replaced. It is a safer bet to look elsewhere for pedals.

Update: Shimano now offer an entry level version of the Spd road pedal called Light Action. The Light Actions have a significantly lower spring tension making it easier to enter and exit the pedals than with the rest of their range.

4. Foot Separation Distance: I’ve often heard U.S. riders refer to this as ‘Stance Width’. That term brings out my inner pedant because standing has nothing to do with it and I like terms to name what they mean. So on this blog at least, Foot Separation Distance it will be. If the feet are closer together than the knees while cycling then there will be a challenge to the plane of motion of the knees. Everyone who rides has at some time sat behind a rider who pedals with knees further from the centre line than are their feet. This occurs because the rider has poor ability to internally rotate their hips. When the rider’s torso leans forward to reach the bars, the hips have to internally rotate within the acetabulum (hip socket) to allow that to happen. If the rider’s hips can’t internally rotate enough, the knees have to splay outwards.

When a rider functions like this, knee pain is a matter of when, not if. How long before onset of pain depends on how long and hard the rider rides, how well they picked their parents and how good their connective tissue is. The solution is to move the feet further apart and / or raise the handlebars. This can be done with pedal axles that are longer than standard. Speedplay produce pedal axles in 1/8″, 1/4″ and 1/2″ (3.175mm / 6.35mm and 12.7mm respectively) longer than standard lengths and Keywin make pedal axles in 3mm and 6mm longer than standard. If that isn’t enough, then pedal spacers in 20mm, 25mm and 30mm are available here singly or in pairs.

A much better solution is to fix the functional issues that cause excessive external rotation of the hips, but this takes time and in some cases is structural (permanent). It also takes an interest that sadly, some knees out pedallers don’t really have while ever there is a mechanical way to eliminate their pain.

In contrast, while I’ve seen knee pain occur with riders who’s knees descended further in than did their feet, it is relatively uncommon (except as a result of collapsing arches) as in most cases, the internal rotation of the hips that tends to accompany this unloads the knees. There is also the practical problem of some riders being so skinny hipped that they cannot get their knees to descend over the centre of the foot on modern road bikes with the wider foot separation distance they have compared to bikes of 20 and 30 years ago.

5. Seat Height: If a rider has their seat too high they will attempt to compensate for this. It is exceedingly rare to see a rider with seat too high sit squarely on the seat and overextend each leg more or less equally. The norm is to tilt the pelvis towards one side; usually but not always the right, protecting that side to varying extents while at the same time significantly overextending the other leg; usually, but not always the left. This is why every bike fitter who listens to their clients is used to hearing complaints of left knee pain more frequently than complaints of right knee pain. If this is you, drop your seat. Forget whatever guff you have been told about “your (included) knee angle has to be within X and Y range” and similar stuff. It is without foundation when it comes to individual cases. There is more detail about this in Seat Height – How Hard Can It Be? and Addendum to Seat Height – HHCIB. It is also worth reading The Right Side Bias for additional detail.

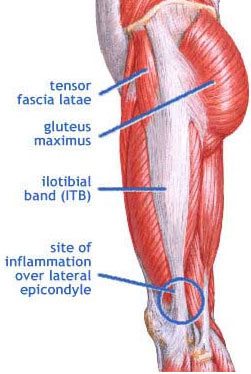

For those who are told by their physio that their on bike knee pain at the lateral epicondyle is caused by a tight ITB (iliotibial band)

they are probably right. What you need to know is that ITB’s usually only become too tight from cycling (as opposed to already being too tight for other reasons) if the opposite hip is dropping. You can roll out the ITB to your heart’s content but if you don’t tackle the root cause; poor on seat symmetry; the problem will continue. The larger question is why are you dropping the hip on the opposite side to your ITB insertion pain at the knee?

Too high a seat height is the most common reason but to that needs to be added the following common possibilities. An uncompensated for short leg or any factor that challenges the stability and symmetry of the pelvis. It could be a dropping arch on one side, a much tighter psoas or adductors (or both) on one side or a whole host of other possibilities. The basic message I am trying to get across is that if you are told your knee pain is due to a tight ITB, take the question one step further and ask yourself or your health professional why the ITB on that side is tight to start with. When that question is properly answered, then you can tackle root causes rather than only the aftermath or fallout from them.

6. Seat Setback: An ideal seat setback balances the loads on the knee joint from the front and the back. The further back the seat, the more the rear chain is enlisted; gluteals and hamstrings. The further forward the seat, the more the quadriceps are enlisted. If there is too much emphasis on front or rear chains with the majority of stresses on the joint all being from one direction, then knee pain from overloading from front or back can result. Often this happens in conjunction with lack of necessary foot correction, poor cleat placement and too high or too low a seat height

7. Bar Position: If the bars are too low or too far away, knee pain MAY be a price paid for the compensatory contortions the rider undergoes in an effort to reach the bars while attempting to maintain stability in their position. All compensatory responses to a challenge to position evoke an asymmetric response. Often this involves a pelvic shift to one side. This in turn causes each leg to extend differing distances to the pedals and each leg to work through a different plane of movement. One or both knees will potentially protest if the rider rides often enough, long enough or hard enough with poor bar position.

FUNCTIONAL CHALLENGES

8. Hip / Lower Back: Pedalling starts at the hips. If your hips aren’t working well, don’t be surprised if you experience knee pain at some stage. The knee is the prisoner of the hip in the sense that it is forced to do what the hip dictates. If hip function is the problem, in most cases knee pain will appear before hip pain.

If you are tight in the lower back, particularly more so on one side than the other, then it is almost certain that you will not sit squarely or near squarely on the seat. As above, this results in each leg working through different planes and reaching different distances to the pedals. Again the knee is the joint most susceptible to injury from this because it can’t move through a variety of planes as the hips and ankles can.

9. Foot / Ankle: Your foot is your contact with the pedal and the body part you use to transfer the power you produce to your bicycle. The knee follows the lead of the foot and ankle. Many people’s knee pain while cycling is in reality a foot or ankle issue.

If your arch drops under load, and many people’s do; or if you have a pronating heel or the less common supinating heel, then there is a potential challenge to the plane of movement of your knee. Most people compensate for these common issues quite well with a variety of compensatory responses. As I say repeatedly on this site, compensations driven by on bike short comings of function are always asymmetric.

An example of this is fresh in my mind because it happened some hours before this section was written. I had a gent today with low / moderate arch feet but with arches that dropped a LOT under load. Basically they collapsed. He also had a shorter right leg, which he knew about but had never done anything to compensate for on the bike. His major complaint was knee pain on both sides. He had seen a succession of health professionals without result until someone suggested “Hey, if this is only a problem on the bike, you need to find a bike fitter!”

I was surprised to see that despite dropping his right hip substantially, he had never experienced on bike low back pain, even though the right hip dropping enough to tilt his pelvis to the right to a degree that caused him mildly overextend his measurably longer left leg. To cut to the chase, he needed a 5mm shim under the shoe of the shorter right leg. I expected this to have a positive impact on his ‘sit with right hip down and drop it further under load, pedalling technique’. It did. Zero.

I then started on foot correction and despite his very low arches he needed the highest black Esoles arch support under the right arch and the 2nd highest blue Esoles arch support under the left arch before the arch support felt like the desirable Level 2 / Mildly Intrusive to him.

Then things got interesting. He needed 1 heel wedge under the right heel in a varus orientation (thick side facing centreline of bike). On the left side he needed 4 heel wedges and 1 cleat wedge in the (much rarer) valgus orientation with thick side facing outwards. Result?

Much improved, almost perfect on seat symmetry and absence of knee pain! The supporting of this gents arches and the correction of the cant of his feet caused him to sit squarely on the seat. It was an inability to do this previously that was loading his knees laterally and causing the pain through patella maltracking. This is only one example, but any shortcoming of foot or ankle function can potentially lead to knee pain.

10. Differences in Leg Length: A story from the past will best illustrate this point. I had a gent named Matt Haran, who was a Sydney A grader (Cat 1) at the time ring me with words to the effect of “Unless you can sort out my knee, I’ll have to give up cycling”. When Matt came in he was dressed in a loose shirt and baggy jeans and his knee wasn’t visible. We had a lengthy chat before he got changed. Part of it it went like this –

ME: “Which knee is it Matt?”

MATT: “The right one”.

ME: “How long has this been going on?”

MATT: “Quite a few years, with the last 12 months being really bad”.

ME: “Have you seen anyone about it?”

MATT: Yes. Several physios and 2 (big name) knee surgeons.

ME: “What did the physios say?”

MATT: “There’s nothing wrong with my knee”

ME: “What did the surgeons say?”

MATT: “That there’s nothing wrong with my knee and that will be $300 thank you”..

ME: “Does it hurt performing any other activity?”

MATT:” No”

ME:”What do you do for a living?”

MATT:” I’m a silk screen printer?”

ME: “What does that involve physically?”

MATT:” A lot of this” (Matt mimes an action of pulling a lever with the right arm and pushing a foot plate with the right leg.)

ME: “How many times a day do you have to do that?”

MATT”: Hundreds. Sometimes thousands”.

ME: (I’m thinking – “Maybe this is the reason”) “Can the machine be modified to allow you to use the other leg?”

MATT: “No.:

ME: “Potentially, are you prepared to find a different job?”

MATT: “No, it’s my business and it’s not big enough yet to employ someone to do that job”.

Matt then got changed into cycling gear. When he came out of the change room he was standing with his left iliac crest 40mm higher than his right side with both knees locked out.

ME: “Matt, has anyone checked you out for a leg length difference?”

MATT: “No. Why?”

ME: “Because your right leg is significantly shorter than your left”

Matt was one of the rare ones with an LLD who sat almost squarely on the seat and murdered his shorter right leg on every pedal stroke. He left with an 11mm shim under his right shoe, which in combination with other changes, was the major reason that he has ridden pain free since. Matt also had an Xray to determine leg length. His right femur was 18mm shorter and Matt had never known, because prior to the previous 12 months, he had never experienced pain or discomfort from it.

Riders with an undiagnosed or uncompensated for LLD will not always hurt on the side of the shorter leg. Sometimes they sit so askew on the seat in an unconscious effort to protect the knee of the shorter leg that it is the longer leg that over extends and experiences knee pain!

Sometimes it is the shorter leg and the internal hip rotation on a bike that causes the knee of the short leg to hurt. There are a plethora of potential compensations. Show me 20 people with the same basic issue and I’ll show you 20 different ways to compensate. This means that sorting out knee pain on a bike is largely an exercise in ‘decompensation’.

There is much more about this in Foot Correction Part 3 – Shimming but simply, a leg length difference must be compensated for with a shim. The shim stack should be determined by what height allows the rider to reach through the bottom of the pedal stroke while at the same time not causing them problems getting the knee of the shimmed leg over top of the pedal stroke. Sometimes a compromise is necessary but it needs to be an effective compromise.

One final word here. It is poor practice to compensate for a leg length difference with a differential cleat position. Many in bike fitting circles believe that if one femur is shorter the other, then the cleat on that side should be further forward to allow the leg to reach further. This is the absolute opposite of my empirical experience and the cause of more problems to more people than I can remember over a large number of years. Cleat position has a marked effect on the muscle enlistment patterns of the leg. By having an obviously different cleat position on each side, you have a different loading of the major muscles involved in applying force to the pedals on each side. If there is a difference in leg length the focus should be on allowing the rider to be as functionally symmetrical as possible, NOT on increasing their functional asymmetry. Each pedal stroke generates a reaction force which is an input to, and potential challenge to the stability of the pelvis on the seat. Differing muscle enlistment patterns caused by differential cleat position exaggerate any potential for on seat asymmetry, not minimise them. If you have a leg length difference and your fitter pushes this approach, ask them why. I would be surprised if you are given an answer that makes any sense, because I’ve yet to hear one.

That differential cleat position is the preferred method of compensating for a difference in femur length by major bike fitting schools shows how little self assessment these schools apply to their recommendations. If they forced their ‘graduates’ to offer their services on a money back if not happy basis (which they don’t), they would quickly find that it is a poor solution.

If there is a leg length difference, use a shim.

11. Riding Too Hard, Too Often

The joint surfaces of the knee are protected by cartilage and synovial fluid. They are a finite resource. Ride long enough, hard enough and often enough without proper rest and the knees can start to show wear and tear for no other major reason. No amount of training has ever made anyone fitter or stronger. It is recovery and supercompensation from the stress of training that makes the athlete fitter or stronger. Ensure you get plentiful recovery, particularly if you have a high training load. If in doubt, more recovery is safer than less.

12. Inflexible Rib Cage

I’m seeing an increasing number of people with knee pain indirectly caused by a rib cage that is tighter and less flexible on one side than the other. In turn this causes pelvic mechanics to be different between sides when breathing deeply while riding hard. It is this change in pelvic mechanics that causes the knee pain because the plane of movement of one or both legs is constantly challenged with every breath and every pedal stroke under load. I know I harp on this but cycling with low propensity to injury is all about being as functionally symmetrical as possible. When you stretch, stretch ALL of your body, not just your legs as many cyclists do. If you don’t breathe efficiently, there will be a cost. And no you won’t suffocate, but if you breathe asymmetrically in a functional sense, knee pain is amongst the issues that can arise.

13. Pre Existing Knee Problems

This can be a tough one. There are a large number of knee problems that may be already present without the rider knowing it specifically. If you have done the rounds with bike fitters for no result with knee pain it is wise to have an MRI and find out exactly what is going on, if anything. Despite me saying this, I have seen horrendous knee injuries that were no barrier to riding a bike pain free providing all the boxes were ticked in terms of decompensating for Challenges to the plane of movement of the knee(s) and providing there was good control of pelvic movement.

Conclusion

Knee pain can occur while cycling for a large number of reasons. There is almost always a solution. The solution may be an on the bike fix or it might involve the sufferer getting off their backside and addressing long overdue problems off the bike as well, but generally speaking, knees are easy. All they want to do is track vertically without being overloaded by Challenges to their ideal plane of movement. That sounds simple and from a bike fitting point of view, generally it is. There are exceptions, but in percentage terms amongst the clients that I see, not many. The basic message I’m pushing in this post is that knee pain occurring from cycling is the knee protesting at being forced to compensate for what is usually a misaligned cleat, or a hip / lower back problem at one end of the kinetic chain, or a foot / ankle problem at the other end. Sometimes a combination is present. Cycling knee problems are rarely intrinsic to the knee.

For those who want to know more about knee anatomy and problems that can arise, a good interactive guide can be found here.

Note: Often, more specific answers to your questions can be found in the Comments below or in the eBooks section and FAQ page.

To learn more about bike fit products offered by Steve, click here.

Do you have a bike fit success story? Please go here to share.

Thank you for reading, return to the Blog page here or please comment below.Comments (9)

Comments are closed.

For clarity you might want to add the word “left” into the second half of this sentence somewhere:

‘He needed 1 heel wedge under the right heel in a varus orientation (thick side facing centreline of bike) and 4 heel wedges and 1 cleat wedge in the (much rarer) valgus orientation with thick side facing outwards.’

Thanks very much for that Michael. I see the mind of a lawyer at work.

Steve

Great article again. The good news is after good support of my arches and 1 wdge rt/lt varus plus dropping my seat 3.3cm so my pelvis is not rocking my anterior knee pain is gone and my feet feel stable on the pedal!

The bad news is my lateral hamstrings bilaterally and ITB bilaterally are hurting. I rode easy for 2 weeks and felt ok but occurred as I picked up intensity. I have tight hips and back and I notice my knees are now out side of pedals especially at the top portion of the pedal stroke. It makes sense to me that this is the cause of pain? Before I was dropping my hips and my knee was driving more medial so was not an issue. If this outside the pedal knee position is the cause do I just measure the distance at the top of the stroke my knee sits outside the pedal using a plumb bob or is there a better way to tell how much wider I need to go.? I of course am following you advice and trying to fix the problem and have gotten stretching for cyclists and Athletic body in balance by Grey Cook. Outstanding. I would encourage everyone to do the movement screen, it is eye opening. I failed a number of them.

Bill

G’day Bill,

You’re right; your ITB and lateral hamstring pain is almost

certainly a result of the knees tracking outside the foot. In a sense, the fact that it is happening bilaterally is a good thing. It means that you are functioning more or less symmetrically which is the hardest thing of all.

To determine how much to move the feet out, yes, use a plumb line. I use my eye and if in doubt experiment with different length pedal axles, or if that isn’t enough, different length pedal extenders. I suggest you drop the plumb line from the centre of the tibial tubercle (bony bump below the knee) which is there the patella tendon inserts to the centre of the midfoot over the highest point of the arch. What ever you are outside that point is what you need to add.

Let me know how you get on. You’re right about the Gray Cook book. The most holistic, best integrated approach I’ve seen to solving restricted range of motion problems by using movement exercises.

I face a 30 mm challenge on the rt and 15 mm left knee outside pedal near the top of the pedal stroke. It appears to be functional as raising the seat decreases these number substantially. However this has practical limitations. What are your thoughts on smaller cranks which decrease the challenge verse using pedal spacers. Are there challenges to the knee or other places in pedal spacers? Are there significant things to think about with a shorter crank. Current crank 175 and I am 6ft 4inches tall.

Of interest the Gray Cooks movement screen predicted this problem as I fail the hurdle step and worse by over an inch on the right. For anyone reading and having bike problems do the movement screen and then work on fixing! His book is great and you can see the screen online. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h8G6jkEf1uI

Thanks

Bill

G’day Bill,

If you change to 170mm cranks your knees will be 10mm lower at

the top of the pedal stroke. That may be enough to solve your problem but I doubt it. I would be putting a 30mm pedal spacer on the right and a 20mm on the left with the left cleat adjusted all the way out to bring the foot all the way in, leaving you with an effective increase in width of the 15mm that you need.

If you are going to do this, Speedplay are by far the best option as they separate the lateral adjustment and rotational adjustment functions completely and are the only pedal manufacturer that does.

Hi, I sent through a bit of an essay on email (not sure if this is the correct thing to do) as I did not want to clog the blog up. In a change in bike I have ended up with inside knee problems – started with right on a 70km ride (5/11) and now both following a ride Sunday 13/11. The fitter tells me it is my pedal technique, however if this is the case why did this not happen with my old bike. Bit scared to start moving lots of things around as I do not have too much cycling experience and am aware there could be many things going on- reading above it could be the cleat/seat height or width between pedals (calf touches big cog and whilst pedal action pretty straight knees possibly tilt in slightly). Much more info on my email, happy to look at video fit, however keen to talk to somebody about the process given my lack of experience. Thanks

G’day Kay,

I’ve answered your email and you should have that in your in

box soon. Once you’ve read it, hit me with any questions you have.

Thanks Steve I will look out for it. Having gone for a run today with no ill effects it has to be something with the repetitive nature of the pedal action!